Barcelona Dispatch

I’m writing from a café in Barcelona, Spain, having spent the last week at the University of Barcelona Faculty of Law, attending and participating in the International Congress on Law and Mental Health. The Congress is a biennial conference organized by the International Academy of Law and Mental Health, held in different major cities. It attracts a global assemblage of scholars, practitioners, judges, and students, drawn heavily from fields such as law, psychology, psychiatry, and social work.

I’ll be flying back to Boston tomorrow morning. In the meantime, I’m sharing my three big takeaway reflections from this little sojourn.

First, among this historically literate group of conference goers, there was a strong sense that we are living in dangerous times. Although the Congress’s focus is not on large-scale politics and statecraft, its big-picture frame envelops the rule of law, human rights, individual and societal well-being, and psychological trauma. Attendees from around the world shared deep concerns about the rise of authoritarian leaders, which frequently infused conversations during session breaks and over meals.

The U.S. presidential campaign loomed large. Indeed, a Canadian friend and fellow conference participant was the first to text me that President Biden had withdrawn as the presumptive Democratic nominee. People are paying attention to what happens, deeply concerned about the critical damage that a Trump presidency would do to democracy, freedom, and the environment on a global scale.

Second, the conference itself served as an important reminder that for academics and others whose work is enriched by sharing our latest research and analyses, in-person gatherings still matter. The people drawn to this conference are doing compelling work in the broad intersections of law, public policy, mental health, and psychology. (For more on that, go here to read a short piece I posted to my professional blog.) While the pandemic, especially, has taught us that presentations can be delivered effectively via Zoom, in-person conferences and workshops create better space for informal conversations that stoke ideas, research, and practice and can lead to future collaborations.

And if the gathering is a good one, meaningful human connections emerge. Through this conference, I have met, and become friends with, so many remarkable individuals.

Finally, on a more personal level, I see changes in how I’m now regarding travel, especially the long-distance variety. This conference marks my first overseas journey since the 2019 International Congress held in Rome. Although the Congress is one of my favorite events, I opted not to attend the 2022 offering in Lyon, France, still feeling uncertain about the COVID situation. But I told myself that the Barcelona conference was the time to get back into global travel mode.

When I was doing my price comparisons, I found that I could save a bit of money by paying for another hotel night in Barcelona to avoid a more expensive return plane ticket. The extra time to enjoy Barcelona would be a bonus. But with the conference having concluded two days ago, and – more importantly — the special people with whom I spent so much time having departed, suddenly this worldly, historic, beautiful city has felt rather empty to me. Indeed, as an unintended experiment, my briefly extended stay has confirmed that (1) my sense of wanderlust diminished during the heart of the pandemic; (2) now when I travel, it’s much more about the who and the why, and less about the where.

And so, instead of spending my last sunny afternoon here doing more sightseeing, I’m hanging out in this café, with my thoughts veering back across the ocean. I’m catching up on emails, looking ahead at my schedule for the coming week, and — at least in my head — morphing back into regular life.

Thirty years in Boston: A contemplation

Thirty summers ago, I packed my bags (and many dozen boxes — mostly books!) for a big move from New York City to Boston. The reason for my move was job-related. I had secured a tenure-track teaching appointment at Suffolk University Law School in downtown Boston.

This was the next step in what was turning out to be an unlikely academic career. In 1991, I returned to my legal alma mater, New York University, as an entry-level instructor in its first-year Lawyering program. That appointment came on the heels of six years of legal practice in the public interest sector. But I didn’t take the job because I thought of myself as an academic in the making. I just figured that it would be an engaging and fun opportunity.

However, I took to teaching immediately. It just clicked for me. Instructors in the Lawyering program were capped at three years, so during that time, I worked hard to make myself competitive for tenure-track appointments. I built a strong record of teaching and started publishing in the field of employment law. During the 1993-94 academic hiring cycle, I entered the tenure-track teaching market and eventually opted to take an offer from Suffolk. Located in the heart of Boston, and regarded as a law school with a historical legacy of opening doors to the area’s working class and emerging middle class populations, it looked like a good match for me.

I didn’t know much about Boston before I arrived here. Beyond a family trip to Boston during my early childhood, a few quick NYC-to-Boston trips to see baseball games at Fenway Park, and interviews at Suffolk Law, I had no on-site familiarity with the city. So, I assumed it was a sort of mash-up between a smaller version of New York City and a big university town, with a diverse, cosmopolitan look and feel.

Oh boy, was I in for a surprise.

Suffolk Law

You see, upon arriving in Boston, I quickly felt like I had moved to a city that seemed stuck in a time warp, characterized by a deep parochialism and struggles with issues of race. It was as if I had somehow traveled back in time some 20 years.

Unfortunately, the culture of Suffolk Law c.1994 was an insular one, very much embracing that regressive look and feel. It surely didn’t roll out the Welcome Wagon to newcomers — especially to those of us who weren’t part of its dominant demographic group.

Even as a pre-tenured professor, I openly confronted aspects of that culture, which led to some very stressful and lonely times. I won’t go into bloody detail here, other than to say that although my concerns were valid (or so agreed the American Bar Association, the Law School’s accrediting agency, in a scathing review of the school’s record of inclusion, prompted by a complaint I filed), they were not well-received by the institution. Accordingly, I knew that had to build a largely bulletproof tenure portfolio, and I did my best to make it so.

In 2000, I would earn tenure — only the second professor of color to do so at a law school that was then almost a century old. I certainly had some hard bruises to show for it. That’s why getting tenure felt more like a fist-pumping triumph over Suffolk than an achievement celebrated in partnership with it. The summer of my tenure year, I visited Maui, Hawaii, for a reunion of cousins. I came back with a large haul of Hawaiian shirts. I called them my “tenure wear” collection, a new wardrobe for teaching class. Out went the dress shirts and ties. I was making a statement: Hello, I’m baaaack!

To my surprise (and perhaps yours, dear reader), I have remained at Suffolk ever since. I still often wear my Hawaiian shirts to class, and my relationship with the institution has sloshed between pretty good and a Facebook-style “it’s complicated.” That said, Suffolk has served as my home base for a successful and satisfying academic career. I get to teach, write, and serve on terms over which I have a fair and appropriate say, protected and empowered by the tenets of academic freedom. That makes me very fortunate.

I hasten to add that there is plenty of good in the institution. Against the backdrop of its virtues and faults, Suffolk has an authentic quality. It is not a stuffy, ivory tower kind of place. It bridges and sometimes negotiates the human dimensions of older and newer Boston. The prototypical Suffolk law student is smart, hardworking, and grounded. Both the Law School and the rest of the university are closely in and of the legal, civic, business, and cultural landscapes of Massachusetts (and New England generally). For someone like me, a city dweller who enjoys operating at the line between research and ideas on one side, and action and application on the other, that makes for a good fit.

My teaching is centered on Employment Law, Employment Discrimination, and Law & Psychology. In three subject-matter areas — workplace bullying and abuse, unpaid internships, and therapeutic jurisprudence (a deep take on law and psychology) — I’ve made significant scholarly, advocacy, and service contributions. None of this was foreseeable when I started at Suffolk 30 years ago. I’ve been able to mature into my true calling during this time.

(For a closer look at some of my work, check out my faculty bio [click here] and my Minding the Workplace blog [click here].)

Boston

As for Boston generally, it has grown on me to a point where I now consider it more than simply an acquired taste. Although the city still exasperates me at times, today I better understand its many complexities. And there are aspects of it that I downright enjoy.

On a personal level, I find it notable that among my circles of friends, most of us grew up outside of Greater Boston — often well beyond Massachusetts. It remains the case that a lot of people born and bred here apparently do not recognize any naturalized paths to genuine Boston citizenship, if you get my drift. (As a Suffolk alumna who fled to the West Coast some 15 years ago quipped, the locals “aren’t taking applications.”)

The city’s challenges with inclusion, race, and tribalism have softened but persist. Boston’s neighborhoods remain fairly divided by their ethnic, racial, social class, and sexual identities. With women, people of color, and LGBTQ folks now asserting their political power, these tensions frequently play out in local elections. Although Boston has long been a solidly Democratic town, the left, liberal, and conservative factions often do battle in the party primaries. Politics remains a bloodsport here.

In keeping with its somewhat bifurcated nature, Boston’s insularity is matched by its intellectual and cultural worldliness. This remains a place where books, history, artistic expression, and innovative ideas still matter. Greater Boston abounds with colleges and universities, medical and scientific research centers, libraries and bookstores, theatre companies, concert halls, cultural and learned societies, and art, history, and science museums. It’s a nerdy place in the best of ways.

History, books, sports, music…and easy accessibility

Several of these intellectual and cultural qualities have a special, ongoing appeal to me.

First, history is ever-present here. In some parts of the city, one can walk on the same streets that Bostonians of the Colonial and Revolutionary eras traversed during their daily lives. Boston’s famous Freedom Trail features historic sites going back to the 1600s.

For a history geek like me, this is all very cool stuff. In fact, I recently joined the board of directors of Revolutionary Spaces, a non-profit organization that oversees two nationally significant historic buildings — the Old South Meeting House (pictured above) and the Old State House — and offers public education programs about freedom of expression, democracy, and the city’s history.

Second, there are books, tons of them. Greater Boston is home to leading public, private, and university libraries. Even in the retail era of online bookselling, the area offers great bookstores, new and used, general and specialized. Two of my favorite places are the central branch of the Boston Public Library, widely recognized as one of the world’s great public libraries, and the Brattle Book Shop, one of the nation’s oldest antiquarian book sellers.

Third, the current century has been a Golden Age for Boston’s professional sports teams. While I still celebrate my Chicago Bears pounding the New England Patriots in the 1985 season Super Bowl, I started following the Pats even before their remarkable run of NFL championships. And I enjoy rooting for the iconic Boston Celtics as well. (Sorry, but when it comes to baseball, I remain a Chicago Cubs fan. I’ve never warmed up to the Red Sox.)

And finally, Greater Boston makes a lot of music, of all varieties. You can go to prestigious conservatories to hone your vocal or instrumental skills. You can start or join a band. You can sing professionally or perform in local shows. If, like me, your music-making aspirations are more modest, then you can take voice lessons at an adult education center and croon tunes to friendly applause at a karaoke club or a piano bar.

These features are enhanced by a city that is both walkable and accessible — the latter via aging, but still decent subway, bus, and commuter rail systems. On this note, Boston has enabled a lifestyle that I discovered and embraced during a collegiate semester abroad in England: City living with a college town vibe, and no car to worry about because I could walk and take public transportation.

Looking ahead

And so, this city that I’ve cursed and struggled with, while coming to enjoy and appreciate, has become my home. Will I ever grow to love Boston? Maybe not, for we have too much of a history for that to happen. But I have come to be strongly “in like” with it, for sure. During my time here, I’ve grown into what I consider to be my best and most impactful self. These surroundings and experiences have contributed mightily to that.

Will the city remain my home for the duration? Well, you won’t see me retiring to a beachside community in Florida, or heading out to some Thoreauvian shack in the woods. But beyond those obvious “not in a million years” possibilities, who knows? For now, in any event, I’m settled in, with plenty more good works left to do, more books to read, and more songs to sing.

***

Editor’s note: This post was slightly revised in August 2025.

Pandemic Chronicles #28: And now, war in Europe

This evening, I watched Lesia Vasylenko, a Ukrainian Member of Parliament and self-described “working mom of 3 lovely humans, lover of freedom, travel and all things green,” tell PBS’s Christiane Amanpour that she and her family are ready to defend themselves and their homeland against the Russian invasion.

MP Vasylenko meant so literally: Along with other elected officials in her country, she now possesses an AK-47 assault rifle and other weapons. Martial law has been declared in Ukraine, and all able-bodied adults are expected to take arms, if necessary, against this unprovoked, unjustified act of Russian aggression.

Appearing in makeup and professional garb befitting an elected official being interviewed by a major news program, Vasylenko nonetheless had a look of grim, determined resolve. I felt a sad moment of dissonance, contemplating her current role as a civilian public servant and parent versus her anticipated role as a member of the home guard fighting Russian troops in the streets of her nation’s capital city.

I also felt a deep sense of admiration. Vasylenko confirmed my strong impression that the Ukrainians are not a soft people. It already appears that Ukrainian armed forces are putting up a valiant fight against a vastly superior military force. At the cost of many lives and considerable destruction, the Ukrainians may make the Russians pay for every foot of ground gained.

A world grappling with a global pandemic and the ongoing specter of climate change has been suddenly confronted by a war in Europe that carries scary echoes of Nazi occupation strategies of the late 1930s and the Cold War that commenced a decade later. This morning, I watched a very sobering webinar briefing by editors and writers of The Economist news magazine that connected the plausible diplomatic dots for how this war could expand deeper into Europe and eventually become a global one. This is an extraordinary perilous time for anyone who cares about democratic rule.

Pandemic Chronicles #13: America votes

As the United States experiences an alarming, nationwide spike in COVID-19 cases, we face an election that will define us for the foreseeable future. The nation’s fundamental integrity and heart quality are on trial. If we do not elect a new President, it is quite possible that the American experiment is over.

Among many other things, I have been saddened and appalled at how the current administration has mishandled the pandemic. Reelecting the incumbent will be the equivalent of imposing a death sentence on hundreds of thousands of unwitting victims, fueled by the dishonesty, ignorance, and cruelty that have defined this man’s nearly four years in office.

The incumbent is doing everything he can to suppress the vote in battleground states and plant seeds of doubt in the election results if he loses. We have never seen anything like this in the modern history of presidential politics.

No other public figure has ever had such a negative effect on my day-to-day quality of life. I feel like I have been forced to endure an abusive civic relationship. The fact that much of my work as an academic addresses behaviors such as bullying, gaslighting, and abuse of power has sharpened my understanding of what we’ve been enduring.

By contrast, I think well of Joe Biden. He is a decent human being and a capable, street-smart public servant. I have long believed that he is the best candidate to win back the White House from its current occupant. When I put my ballot in the mail a few weeks ago, I was happy to vote for him and Kamala Harris. I pray that I voted for the winning ticket.

The weeks to come will determine the future of America’s soul, not to mention our ability to defeat and recover from a deadly pandemic. We live in momentous times.

***

Cross-posted to my Minding the Workplace professional blog.

Homecoming 2016

Sometimes we can go home again, and if we’re lucky, the experience can be even sweeter than the first time around.

In a year of ups and downs, one of my most memorable, positive experiences was returning to Valparaiso University in northwest Indiana, my undergraduate alma mater, to receive an Alumni Achievement Award during fall Homecoming festivities. The awards presentation ceremony was part of a Sunday Homecoming service in VU’s Chapel of the Resurrection, followed by a luncheon in the new student union.

From the vantage point of my 1981 graduation from Valpo (the school’s informal monicker), this was an unlikely return to campus. As an undergraduate, I was a department editor and writer for The Torch, VU’s student newspaper. At the time, The Torch editorial board was something of a campus rebel cell, post-Sixties edition. Though too young to have experienced the student movement, we were given to questioning things and mildly anti-authoritarian by nature. Whether it was creeping vocationalism that threatened the liberal arts, behavioral excesses in fraternity behavior (“Animal House,” a wildly popular movie during that time, was influential), or challenges with various diversities on campus, we believed that our editorial mission was to take on the university for its supposed shortcomings.

Some of our critiques were insightful, the products of bright young minds applying the lessons of a liberal education to the institution that provided them. Others were more sophomoric, using the print medium to launch a few post-adolescent salvos. Mine mixed the two categories in a sort of hit-or-miss fashion. In any event, by the time Commencement rolled around, I had internalized those grievances and smugly assumed that I had outgrown the place.

Accordingly, when I first informed long-time friends that VU’s Alumni Association would be recognizing me at Homecoming, several humorously noted the irony of the sharply critical student returning to campus decades later as a grateful middle-aged award recipient. (Several senior VU administrators back in the day wouldn’t have predicted this development, either, though with less bemusement.)

However, my relationship with VU had been in a state of positive change for some time, marked by a steadily growing appreciation for the excellent education I received there and for friendships forged via experiences such as The Torch, a life-changing semester abroad, and everyday dorm life.

In fact, I was extremely blessed to have a group of friends, mostly fellow alums from our close-knit Cambridge, England study abroad cohort and several of their spouses, joining me for the Homecoming award ceremonies. (I know that “blessed” is an overused term, but that’s how I felt.) During my extended visit, which included time as a visiting scholar at VU’s law school, I also enjoyed welcomed opportunities to reconnect with other friends from my VU days.

Returning to campus was both nostalgic and slightly disorienting. For many years after our graduation, Valpo’s physical landscape had remained basically the same. However, during the past decade or so, new buildings have sprouted up seemingly everywhere, and even some streets and pathways on campus have been rerouted. On Homecoming weekend, our shared memories mixed with exclamations over how building so-and-so had disappeared. The downtown area of the small city of Valparaiso also had changed markedly, with a much greater variety of restaurants and public spaces. It was fun to make these discoveries with my friends, as if we were once again undergraduates exploring England and the European continent — even if this time we actually were in America’s heartland.

Valparaiso’s longstanding affiliation with the Lutherans and the importance of faith traditions in general are core parts of its institutional mission. During the early decades of the last century, Valpo was a secular, independent university well known for its vocational training. Hard times would visit the school, however, and its survival was in question until the Lutheran University Association stepped in to buy it in 1925. Among the continuing manifestations of this association are daily Chapel services, open to those of any denomination.

In my case, it would be an understatement to say that I was not a frequenter of Chapel services as a collegian. However, at Homecoming I now found myself unexpectedly moved by the fact that the University would devote a Sunday worship service to recognizing its graduates. As a denizen of higher education, I know well the differences between giving obligatory nods to alumni/ae honorees and showing genuine appreciation. This was a very touching example of the latter.

Luncheon for awardees, family, and friends. L to R, Anne, Mark, Hilda, DY, Joanne, Scott, Sharon, and Don (Photo: Chet Marshall)

The memories stoked by this weekend went well beyond student life and into the realm of world events that transpired around us as undergraduates. Among other things, little did we know at the time that we were bearing witness to the emergence of at least two major mega-trends — the primacy of the Middle East as an American foreign policy hot spot and the conservative resurgence in American politics — that would help to define our civic lives well into middle age.

In November 1979, young Islamic revolutionaries took some 60 American hostages during a seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The Iranian hostage crisis, as it soon would be tagged, would endure for nearly fifteen months until the hostages were freed in January 1981. During that time, ABC journalist Ted Koppel became a national media figure with his daily hostage crisis updates on “Nightline,” a program that followed the late night local news. At Valpo, many of us tuned in each night in our dorm rooms, watching on our rabbit-eared portable television sets.

As undergraduates, we watched Ted Koppel’s daily updates on the Iranian hostage crisis (screenshot from abcnews.go.com)

The fall of my senior year also marked my first opportunity to cast a general election ballot for President. Jimmy Carter was the Democratic incumbent, having successfully run on an anti-Washington platform in 1976. However, change was brewing in the form of a conservative movement that would sweep Ronald Reagan and a group of new Republican Senators and Representatives into office.

I was deeply into politics at the time. In fact, I was majoring in political science and planning to go to law school as preparation for an eventual political career. My own political views were in a state of flux, moving from right to left. In terms of presidential candidates in 1980, I had become enamored of an Illinois Congressman named John Anderson, a one-time conservative whose own views had become more liberal over the years. Anderson ran as a liberal Republican in the spring presidential primaries and then decided to leave the GOP to pursue an independent candidacy in the fall. I would serve as the Northwest Indiana coordinator for his independent campaign, a volunteer assignment that said less about my political organizing skills and more about the green talent the campaign had to rely upon in certain parts of the country.

Looking back, I now understand that Anderson’s departure from the Republican Party represented a harbinger of things to come. The 1980 election marked the beginning of the GOP’s rightward turn and a coming out party for a conservative movement that has dominated much of American politics since then.

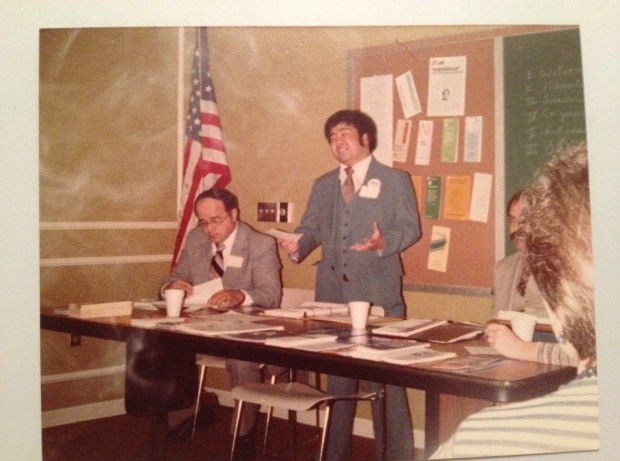

In my best polyester suit, I represented the Anderson campaign in a 1980 presidential debate sponsored by the Porter County, Indiana chapter of the American Association of University Women.

My collegiate years at Valpo felt heavy, as if I was carrying the weight of my future on my shoulders, fueled by a growing desire to explore life outside of my native Indiana and anxieties over where I would be and how I would fare. In 1982 I would decamp to Manhattan for law school at New York University, thinking that Indiana would be viewed mainly from a rear-view mirror.

Fast-forward to 2016: During a moment in the alumni hospitality tent at the Homecoming football game, I remarked to VU President Mark Heckler that it felt very light to be back on campus — a stark contrast to my emotional center of gravity as an undergraduate.

Indeed, this return to VU was accompanied by gifts of appreciation and maturity and was made especially meaningful by the company of dear friends who now richly deserve the label “lifelong.” A homecoming can’t get much better than that.

Wanna run for President? You can!

In a piece for the Boston Globe (registration may be necessary), Astead W. Herndon reports that over 500 individuals have registered with the Federal Election Commission (FEC) as Presidential candidates. You see, while it may take lots of political clout and mega-millions in campaign monies to get elected President, it basically requires filing the required FEC paperwork in order to be a candidate. It sounds easier than filing your taxes!

Of course, there’s more to it than that if you actually want to get votes, even those of friends and family. States have their own petition requirements and filing fees to get your name on the ballot, and to do that you’ll need campaign cash, connections, and a host of volunteers.

But if you’re just looking for a personal platform, you can register with the FEC, declare yourself a candidate, and rely on our Digital Age, low-cost options to start campaigning. For example, Herndon reports that one fringe candidate is running his campaign with “a website, a Facebook public figure page, and a similar profile on LinkedIn.”

I first became aware of the plethora of unknown Presidential aspirants back in college, when one of my political science professors shared with me some campaign brochures that he had collected from fringe candidates. I sent away for more, and eventually I wrote a piece on these indie wannabes for my college newspaper. A few were known quantities who had long ago faded into the political woodworks. (If the name “Harold Stassen” rings a bell, then you know what I mean.) Others were earnest citizens from various walks of life, and a good number had single-issue axes to grind. Naturally, some were simply a bit wacko.

Throughout college I was bound and determined to launch a political career and had been very active in local political campaigns and in student government. At a time in my young life when political hype fascinated me more than policy substance, I was drawn to the ease with which someone could become a candidate for America’s highest office.

Now, I’m not about to toss my own hat into this very fringed ring. I long ago jettisoned ambitions of a political career, including quixotic runs for big offices. But there’s enough of a political junkie in me still remaining to have fun thinking about what my platform and message might be. In fact, it’s pretty liberating to think about this without the need for posturing, positioning, fundraising, and currying favor. As long as you don’t care about winning, you can pretty much say what you want. Hmm….

Throwback Thursday: Where were you when Nixon resigned?

For those of you around during August 1974, where were you during when President Richard Nixon resigned from office in the midst of the Watergate scandal?

At the time, I was in high school, heading into my sophomore year. That night I happened to be watching a football game. The Jacksonville Sharks were playing the Hawaiians, both of the fledgling World Football League, an upstart, ragtag operation that was challenging the established NFL. The game was interrupted by Nixon’s resignation’s speech, which made for an odd return to the televised game action following such a momentous event!

For readers too young to understand the Watergate scandal, or for the sprinkling of international readers thankfully spared the ongoing saga back then, Nixon got in trouble when his Administration was linked to an illegal break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington D.C.’s Watergate Hotel during the 1972 election campaign. As is so often the case, the cover up was worse than the initial sin, and it led right to the Oval Office.

The Washington Post took the lead on investigating the Watergate scandal, and it served to launch the careers of two unknown reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

The movie “All the President’s Men,” starring Robert Redford (Woodward) and Dustin Hoffman (Bernstein), manages to tell the story of the Post‘s investigation with a sense of detail and drama that conveys the gravity of this historic event in American government and politics. It still holds up as an excellent movie.

Throwback Thursday: Volunteering for the 1980 Presidential campaign of John B. Anderson

Yup, that’s me, speaking at a 1980 presidential debate sponsored by the Porter County, Indiana chapter of the American Association of University Women, wearing my best polyester suit. Note the cigarette smoke appearing in the photo!

As the boxes of papers in my condo unit storage area attest, I tend to save stuff! This stuff includes a small pile of mementos from the first Presidential candidate I ever supported and voted for, John B. Anderson of Illinois. I spent countless hours working as a volunteer for Anderson’s 1980 independent campaign, and it is one of my most memorable college experiences.

I’ve written earlier that during college and law school, I had every intention of launching a political career, so much that I was obsessed with the machinations of campaigns and elections. During this time, and especially through college, my own political views were very much in flux. I started college as an independent-minded Republican and finished as an independent-minded Democrat. But it’s also safe to say that my positions on issues were more knee-jerk than principled and well thought-out. regardless of whether I was leaning right or left!

Since then, my views have usually come out on the liberal side, but as to individuals I admire and respect in public life, I find myself drawn to people of character and integrity in ways that may transcend political partisanship. This may signify that I have come full circle, because John Anderson had those qualities in abundance.

In a way, my own political journey tracked that of Anderson, who for most of a long career in the House of Representatives was a strong conservative, rising to party leadership positions and representing a Rockford, Illinois district that returned him to office time and again. But in the wake of Vietnam and the social upheaval of the 60s and early 70s, Anderson began moving to the left, to the point where he entered the 1980 GOP primaries as a “liberal Republican,” a designation that would be virtually impossible today.

Anderson made a splash in the primaries and was gaining a following that cut across political lines, but he knew that his chances of winning the nomination — eventually secured by Ronald Reagan — were practically non-existent. So he decided to mount an independent Presidential campaign. He engaged in the arduous effort to get on the ballot across the country, and he picked a running mate, former Wisconsin Governor Patrick J. Lucey, a Democrat.

Although polling data showed Anderson with double digit support through the summer of 1980, he faded in the fall and garnered 7 percent of the November vote, far behind Reagan and the Democratic incumbent, Jimmy Carter.

I served as the Northwest Indiana coordinator for the Anderson/Lucey campaign, an area covering Lake and Porter counties, two fairly heavily populated areas of the state. My position signified the degree to which the campaign had to rely on green volunteer talent. I coordinated a small organization of volunteers, served as a representative to the statewide campaign committee, participated in a couple of local debates, and even did some local radio interviews.

Some of the mementos pictured above are self-explanatory, but let me say a bit about three of them:

(1) The ALL CAPS letter on the left is a mailgram sent by Vice Presidential candidate Patrick J. Lucey to core Indiana volunteers, thanking us for a furious and ultimately successful petition effort to put him on the state’s November ballot. Lucey had been added to the ticket as Anderson’s running mate after petitions for Anderson had been submitted, so the Indiana courts required us to mount a second petition effort to secure his place as the VP candidate on the ballot.

(2) The newspaper article at top is a summer 1980 piece by the Gary Post-Tribune, featuring our small band of Anderson volunteers. It was one of my earliest press interviews about anything, and I recall how nervous I was speaking to the reporter! The article mentions an older couple, John and Kim Glennon, who served as den parents to our young volunteer group. Mrs. Glennon had attended law school with Anderson at the University of Illinois.

(3) The letter on the right was sent to key Anderson supporters after the November election, thanking us for our efforts on behalf of the campaign. I didn’t know if Anderson personally signed it or whether a robo-signing machine was used, but it was nice to receive the letter after working so hard for the campaign.

The 1980 election will forever be associated with President Reagan’s election and the nation’s rightward political shift, but I believe that Anderson’s story also symbolizes that change. After many years as a Republican loyalist, Anderson’s politics were moving left as his party’s positions were moving right. Anderson’s campaign platform was a mix of liberal social positions, strong support for workers’ rights, and moderate-to-liberal economic policies. His departure from the GOP anticipated the sharper ideological divisions that continue to confront America today.

In the years following the election, Anderson did a lot of teaching and lecturing, eventually becoming a law professor at Nova University in Florida and serving in leadership positions for various advocacy groups. He’s in his early 90s now. I’m not sure if he is still active as a teacher and advocate, but I hope he knows that his campaign made a strong impact on those of us who were fortunate to be a part of it.

Bloody politics

I just finished reading Mark Leibovich’s This Town (2013), a bestselling “insider” look at political life in the nation’s capital. It’s bitingly funny at times, as one might expect such a book to be, and it provides a fix for recovering political junkies like me.

It’s also a reminder of a path I chose not to take.

You see, reading about politics is a far cry from my aspirations of decades ago, when I was an ambitious student government pol in college and planned to go to law school as a springboard into the real thing. As an undergraduate at Valparaiso University in Indiana, I was elected to various student senate positions, and I volunteered regularly for political campaigns. I managed a successful upset campaign for a town board seat in northwest Indiana, and I served as an area coordinator for the 1980 independent presidential run of John B. Anderson.

Of course, I also was a political science major, and it so happened that the poli sci department at Valparaiso was comprised of dedicated teachers who stoked my fascination with politics. In particular, Professor James Combs, quite the political junkie himself, was teaching and writing up a storm about political communications, which played right into my obsession with campaigns and elections.

My interest in politics continued through law school and beyond. As a young lawyer during the late 1980s, I was an officer in a reform Democratic club in Brooklyn, and it served as a very on-the-ground introduction to the gritty realities of New York politics. (I recall discovering pages and pages of forged ballot access petition signatures filed by one of our opponents, marveling at their sheer chutzpah.)

But some 23 years ago, I stumbled my way into teaching. I returned to my legal alma mater, New York University, as an entry-level instructor in its innovative Lawyering skills program for first-year law students. I knew immediately that I enjoyed being an educator, and that experience turned out to be the start of an academic career. In fact, I’m now in my 20th year of teaching at Suffolk University Law School in Boston.

Today, I’m hardly removed from politics. My work in drafting and advocating for workplace bullying legislation puts me in regular contact with legislators and their staffs. Two years ago I finished a term as board chair of Americans for Democratic Action, a liberal policy advocacy organization based in D.C. And though my politicking these days is limited primarily to occasional campaign contributions, I follow electoral politics fairly closely.

But the world portrayed in Leibovich’s This Town, however embellished to attract more readers, is not for me. There are a lot of good, honorable people in politics, a fact we dismiss too easily in this cynical age. But politics is a bloodsport, and it requires a certain dispositional DNA to play the game for the long term without it becoming debilitating. When I think back to my collegiate ambitions, I now understand that I enjoyed reading and writing about politics more than being in the thicket of political life, even as the latter appealed more directly to my ego and insecurities at the time.

Okay, so the world of academe is hardly apolitical, and it can get as petty and nasty as any political brawl. (I sometimes quip that the real untold Biblical story is how God banished Adam & Eve to a faculty meeting as punishment for their transgressions.) That said, the focus of academic work itself is more on teaching, writing, and public education, and that’s more to my liking than the day-to-day work of political life.

Still, please do excuse me if I get a little charged every four years over news coverage about the Iowa caucuses or the New Hampshire primary. It remains neat stuff to me, albeit from a distance.

Recent Comments