Classic movie report: August 2015

I declared as one of my New Year’s resolutions that I would watch more classic old movies, so each month I’m devoting an entry to how I’m doing with it. This month I dug back to 1976 for a couple of really solid films.

Aces High (1976) (3 stars out of 4)

Although I’m a big fan of historical dramas, I somehow managed to miss Aces High until now. It’s an underrated war movie about British fighter pilots during the First World War. Malcolm McDowell, Christopher Plummer, Peter Firth, and Simon Ward are the stars of an ensemble cast.

The movie features very good aerial scenes (no irritating CGI here) and interesting if sometimes cliched personal dramas. This film was a pleasant surprise, a random streaming discovery from Netflix. It stands well above two more recent WWI aviator movies, Flyboys (2006) and The Red Baron (2008).

The Omen (1976) (3.5 stars)

The Omen is one of my long-time favorites, a movie that first sent chills up my spine back in high school and continues to do so. Gregory Peck and Lee Remick co-star as the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain and his wife. They have a son, and let’s just say that he’s a young man of Biblical qualities, and not the good kind.

Yup, there are some plot implausibilities that are stretches even for horror film. But it delivers on goosebumps. Suffice it to say that after watching The Omen, you’ll be wary of surprise nannies, little boys with a head of steam, and priests bearing bad news.

Latest binge view: “The Knick” (season one)

Last weekend I plowed through the ten episode first season of The Knick, a Cinemax drama set in a fictitious Manhattan hospital during the early 1900s. It stars Clive Owen as Dr. John Thackeray, a brilliant, driven, and cocaine-addicted surgeon. It has a great ensemble cast playing various doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, ambulance drivers, and board members.

The Knickerbocker hospital serves Manhattan’s poor and working class, and its medical staff attempts to be on the vanguard of treatments, diagnostics, and surgical techniques. It makes for sometimes gruesome scenes, and for this reason some readers might want to avoid it. (Think a turn of the century version of ER and you’ll have some sense of what I mean.)

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of The Knick is how it portrays the evolution of health care as it moves out of the Victorian Age. Even those generally familiar with the history of medicine will appreciate the sense of drama in storylines about new and experimental approaches to health care.

The Knick also depicts treatments that by today’s standards are wrongheaded and even barbaric. Ambulance drivers are profiteers and body collectors. Issues of race are dealt with bluntly, including the presence of an African American surgeon whose knowledge and experience are completely dismissed when he joins the surgical staff.

And finally — no spoiler alert necessary — the last scene of the final season one episode is simply brilliant.

My cable subscription doesn’t include Cinemax, so I’ll have to wait for the season two DVDs to jump back into the world of the Knickerbocker Hospital. I can’t wait!

Classic movie report: July 2015

I declared as one of my New Year’s resolutions that I would watch more classic old movies, so each month I’m devoting an entry to how I’m doing with it. This month’s selections have a distinctly Austrian flavor to them, inspired by a week-long visit to Vienna this month to participate in a conference on law and mental health.

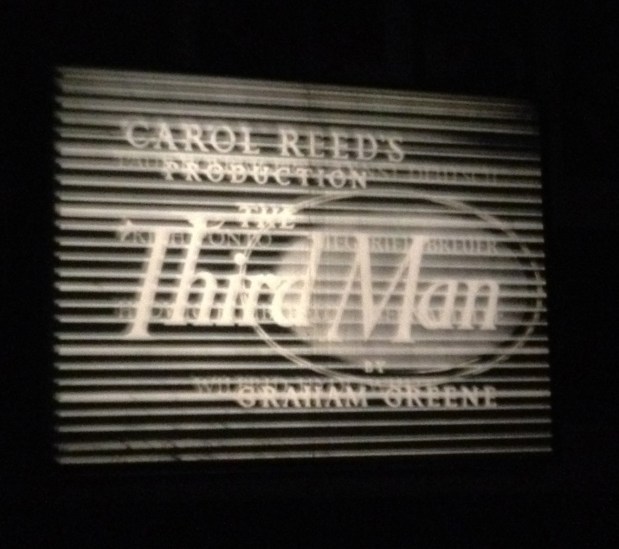

The Third Man (1949) (4 stars out of 4)

This is widely recognized as one of the all-time best movies, a story set in postwar Vienna, with Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Trevor Howard, and Alida Valli in starring roles. IMDb neatly sums up the plot without giving anything away:

Pulp novelist Holly Martins travels to shadowy, postwar Vienna, only to find himself investigating the mysterious death of an old friend, black-market opportunist Harry Lime.

The other star is Vienna itself, largely shorn of its glorious beauty and instead portrayed as city of intrigue and recovery in the years following the Second World War.

My first sightseeing visit in Vienna was not to an art museum or classical music venue, but rather the small Third Man Museum, dedicated to the movie and life in postwar Vienna. It was time very well spent. Here are some photos from the museum:

Wonderful zither concert by Viennese musician Cornelia Mayer…again, if you know the movie, then you know this instrument!

The Sound of Music (1965) (4 stars)

This beloved, iconic movie musical, set in pre-war Salzburg, is about as wide a contrast from The Third Man‘s depiction of Austria as one could imagine. Starring Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, the renowned classic is celebrating the 50th anniversary of its release. In addition to offering songs that are firmly embedded in our popular culture, the film makes maximum use of the beauties of Salzburg.

Back in 1981, after finishing a semester abroad program in England, I made a quick tour of the European continent, and Salzburg was one of my stops. Even though at the time I had never seen the movie, I allowed myself to get dragged onto The Sound of Music bus tour by one of my traveling companions. While she was thrilled at every recognizable location from the movie, I just kept taking pictures, figuring that someday I’d watch the movie and then flip back to my photos to compare. I’m glad I did.

Here are some of those old snapshots.

***

Photos: Third Man Museum (DY, 2015); Salzburg (DY, 1981).

Heaven for a history geek: A David McCullough book talk

One of the best things about living in Boston is that a lot of authors do book talks here, including many great writers of history. I just got back from one of them, a talk by historian David McCullough about his latest book, The Wright Brothers (2015), a story of brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright, who invented and flew the first successful airplane in 1903.

McCullough spoke in Cambridge as part of the Harvard Book Store speaker series to a packed house at the First Parish church.

McCullough is one of America’s foremost popular historians, and he is one of my personal favorites. His love of history pervades his books and his public appearances. In addition to being a master storyteller in print, his gravelly but gentle voice and a contagious enthusiasm for his subject matter add a magical quality to a talk or documentary.

McCullough confessed that before he started his research, he knew little of the Wright Brothers’ story beyond the basics: Two brothers, owners of a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, would go on to build and fly the first successful airplane, flown at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

However, as he dug into their story, he learned about how Orville and Wilbur were raised in very modest surroundings by a missionary father who believed very strongly in the power of reading, how their sister Katharine strongly influenced and supported their work, and how an intense devotion to teaching themselves the science and mechanics of flight led to their success.

It is clear that McCullough came to admire his subjects, for both their intelligence and their character. The Wright Brothers, he made clear during his talk, had the right stuff. He allowed himself to make broad connections, suggesting that great history is not just about politics and war. He compared the brilliant inventiveness of the Wright Brothers to that of composer George Gershwin.

During his prepared remarks and a lively Q&A, McCullough waxed eloquent about the importance of historical literacy. He said that history can be a “wonderful antidote” to the hubris of our present era. He noted that developments we take for granted today may be regarded as breakthroughs many years from now, adding that prognosticating about the future may be futile. “There’s no such thing as the foreseeable future,” he quipped.

David McCullough is a national treasure, as exemplified by tonight’s audience thanking him with long, warm rounds of applause and a standing ovation. It was just so much fun to be in the presence of this great historian and storyteller.

Classic movie report: April 2015

I declared as one of my New Year’s resolutions that I would watch more classic old movies, so each month I’m devoting an entry to how I’m doing with it. Here are my two selections for April:

WarGames (1983) (3.5 stars out of 4)

WarGames may not be a great movie, but I find it so eminently entertaining and re-watchable that I have to give it 3.5 stars.

Matthew Broderick stars as David Lightman, a young computer maven and high school student who manages to hack into the U.S. Defense Department’s new super computer. In doing so, he engages its artificial intelligence in a way that almost causes a nuclear war. Ally Sheedy plays his adorable sidekick, Jennifer Mack, and the two become partners in crime.

The chief adults in the movie are Dabney Coleman as Dr. John McKittrick, the computer expert who persuaded the government to adopt the new mainframe, and John Wood as Dr. Stephen Falken, a withdrawn scientist whose theories become central to the story.

WarGames has its serious side. On occasion it has been cited by scholars as an excellent pop culture depiction of how Cold War mentalities and an uncritical worship of the “wisdom” of computer technology could lead us down a disastrous path.

But it’s also a ton of fun. Broderick and Sheedy are well-paired in this movie, and their scenes together include some hilarious high school moments and (now) nostalgic depictions of early personal computing and video games.

For me it pushes nostalgia buttons as well. I first saw WarGames when it was at the movie theaters in the summer of 1983. It was right after my first year of law school, and I was living in one of the law school dorms. In consultation with a couple of friends, we picked it out of the Village Voice listings and decided to give it try. I enjoyed it from the opening scenes, and I’ve watched it many times since then.

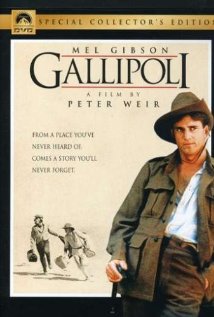

Gallipoli (1981) (3.5 stars)

Mel Gibson and Mark Lee co-star as young men from Western Australia who enlist in the Australian Army during the First World War. They find themselves deployed to the Ottoman Empire (now modern day Turkey), as part of the Allied Gallipoli Campaign in 1915.

The film starts as something of a buddy movie with some 80s-style artistry, but by the time the climactic battle scenes arrive, it is a story of the terrors of trench warfare. It also reinforces a common First World War theme of utter futility, with senior officers repeatedly ordering their troops to go “over the top” in charges met by murderous machine gun fire.

Gallipoli isn’t the best of the WWI movies, but it belongs on a list of “should watch” films about the war, including the classic All Quiet on the Western Front and the excellent Paths of Glory.

In terms of 20th century history, I relate more strongly to the Second World War than to the First, but that gap is closing as I learn more about the Great War during this period of centennial observation (1914-18). It is a fascinating historical story, one infused with a haunting sense of loss due to the brutality of trench warfare, as well as the knowledge that the terms of surrender eventually imposed on Germany would help to fuel the rise of Nazism in the decades to come.

My fascination with Abraham Lincoln

From my modest Lincolnania collection: Reprints of Harper’s Weekly following the assassination and the playbill from the fatal night (Photo; DY)

One hundred and fifty years ago today, President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) died of a gunshot wound to the head, fired by Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth the night before at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. It’s a story that gives me chills.

I remember when I realized that Abraham Lincoln is one of the most fascinating, compelling figures in history. It was 1986, the year after I graduated from law school, and I made a quick trip to Washington D.C. to see friends and play tourist. The latter included visits to the Lincoln Memorial, Ford’s Theatre, and the Petersen House across the street from the theatre, where a wounded Lincoln was carried after the shooting and cared for until he died.

Ford’s Theatre and the Petersen House were especially powerful and haunting; I simply felt something there about the tragedy, sadness, and enormity of what happened. I bought a couple of Lincoln biographies and dove into them. By the time I returned home to New York, Lincoln was very much on my historical radar screen.

The draw of Lincoln has continued for me, coupled with a like fascination over America’s Civil War. It is a deep interest shared with friends. For example, in recent years, I’ve accompanied my long-time friends and fellow history buffs the Driscolls (yeah, the whole family — too numerous to list out here!) to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, as well as to other Lincoln sites in the city, including Lincoln’s law office.

Among great historical figures, the most compelling thing about Lincoln to me is his humanity. We know today that he suffered from severe bouts of depression, dating back to his earlier years. With his humble roots, we might call him a self-made man. He became a lawyer largely by private study, in the days when one could become an attorney without going to law school.

The United States was breaking apart between North and South when he assumed the Presidency in 1861. He carried the weight of the world on his shoulders during the Civil War, while dealing with the death of a young son due to typhoid fever and the devastating effects of that loss on his wife, Mary.

Perhaps to counter his sorrows, Lincoln had a sharp sense of humor and loved to tell humorous stories to punctuate his points, to the exasperation of more “refined” senior advisors and Cabinet members. His beliefs about race, while in some ways advanced for his time, would fall short of modern standards of political correctness. He was also a shrewd politician who knew how to get things done, even if it meant breaking bending the rules a bit.

So many great historical figures seem personally inaccessible to me. But it seems that Lincoln could carry on a conversation with just about anyone, and if we were to go back in time and bump into him on the streets of Washington (which he often walked, without security escort), I bet that we could strike up a chat with him, too.

***

Related post

“Had Anne Frank been able to survive for just a few more weeks…”

It has been one of history’s heartbreaking “what ifs”: What if Anne Frank had been able to survive the typhus that would claim her for just a few weeks longer, when the Allies liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp where she was imprisoned? Would she have recovered under the care of the Allies? If so, what would’ve become of her life and her diary?

It had been estimated that Anne and her sister Margot died in late March of 1945, and the Allies liberated the camp on April 15. Hence, many have contemplated the excruciating possibility that the Frank sisters barely missed being rescued.

Now, however, the Anne Frank House museum in Amsterdam estimates that she died sometime in February. From an Associated Press story by Mike Corder (via Yahoo! News):

Anne likely died, aged 15, at Bergen-Belsen camp in February 1945, said Erika Prins, a researcher at the Anne Frank House museum.

***

But [Prins] said the new date lays to rest the idea that the sisters could have been rescued if they had lived just a little longer.

“When you say they died at the end of March, it gives you a feeling that they died just before liberation. So maybe if they’d lived two more weeks …,” Prins said, her voice trailing off. “Well, that’s not true anymore.”

You can read the full article for details on how the new approximate date of their deaths was determined.

The story of Anne Frank can do numbers on us. We may engage in rescue fantasies, wondering how Anne could’ve held on just a little while longer, until the camp was liberated. We may speculate, with twinges of guilt, whether her diary would have ever been published had she made it through the war.

So now the likelihood is that when Anne and Margot Frank were suffering from typhus, liberation was not just a few weeks away.

This can trigger questions that cross into the religious or metaphysical, with still more discomfort attached: Did Anne Frank die so that millions could be moved by her diary?

***

In 2013 I visited the Anne Frank House museum. I was participating in the biennial Congress of the International Academy of Law and Mental Health, held that year in Amsterdam, and this was the one “must see” item on my list for a first-ever visit to the city.

The exterior pictured above doesn’t give you a hint at what’s inside. The interior has been recreated to show us how Anne and seven others lived in hiding for some two years. I am among countless others to say it, but it was a very moving experience to stand in the same cramped spaces of the “Secret Annex” where they lived before they were discovered and arrested.

For me, the most chilling part of the tour was walking up the long, narrow stairwell to the Annex, located behind the moving bookcase that covered the entrance. It was the same walk their captors took to find and arrest them. Of course, it also was the stairwell taken by the residents of the Annex as they were being escorted out of their hiding place.

***

You may take a virtual tour of the Annex here.

Classic movie report: March 2015

From “The Big Parade” (l to r): Tom O’Brien as Bull, John Gilbert as James Apperson, and Karl Dane as Slim

I declared as one of my New Year’s resolutions that I would watch more classic old movies, so each month I’m devoting an entry to how I’m doing with it. This month, the weather has warmed up slightly, and much of my limited TV time has been devoted to great dramas such as Downton Abbey and The Americans, but here are two oldies that I was able to sneak in:

The Big Parade (1925) (4 stars out of 4)

I don’t know how this one escaped my attention for all these years. King Vidor directed this 1925 silent classic starring John Gilbert as James Apperson, the son of a wealthy American family who joins the Army when the U.S. enters the First World War. It’s an excellent film that mixes humor, romance, drama, and tragedy.

While deployed in France, Apperson meets a village farm girl, Melisande. Their wartime romance captures well how the silent movies could tell a story.

The “big parade” is not referring to a procession featuring the victorious heroes. Rather, it’s the march of men and war materiel going to and from the front. And as these photos attest, the ground war would be joined by a new weapon of destruction, the airplane.

Strategic Air Command (1955) (3 stars out of 4)

Jimmy Stewart stars as an aging major league baseball star and a WWII veteran pilot who is called back into active duty with the Air Force to help develop America’s post-war bomber command. June Allyson plays his treacly sweet wife. It’s more of an interesting technicolor artifact than a genuine classic, reflecting a 50s Hollywood take on the Cold War. The perceived need for strategic bombing capacity helps to drive the story, but oddly there’s nary a mention of the Soviet Union or any other communist nation.

The flight scenes are the highlight of the movie. Aircraft geeks may especially enjoy watching the B-36 bomber, a slim, long plane with a huge wing span, powered by six propellers and four retrofitted jet engines. The B-36 preceded the B-52 as America’s primary long-range bomber, which happened to arrive on the scene the year the movie was released.

The flight scenes provide the drama, for the acting among the main characters is pretty stiff, even given that we’re talking about a story set in the military. For Stewart, this role somewhat reprised real life. He was an American bomber pilot during the Second World War.

(All screen shots by DY, 2015)

Throwback Thursday: Discovering Jack Finney’s “Time and Again”

You may have to be a bookworm to fully appreciate a soggy, nostalgic Throwback Thursday post about, well, reading a book, but here it is: About 30 years ago, I discovered Jack Finney’s Time and Again (1970), an illustrated novel about a Manhattan advertising artist named Si Morley who is enlisted in a U.S. Government project experimenting with time travel.

No spoiler alerts are necessary to give you a preview. Let me first quote from the back cover of my paperback edition (pictured above): “Did illustrator Si Morley really step out of his twentieth-century apartment one night — right into the winter of 1882?” I’ll say no more about the story, except to say that if you love New York City and enjoy time travel stories, then this book is for you.

I discovered Time and Again in 1985. I had not heard of the book when I kept glancing at it during repeated visits to Barnes & Noble’s giant sale annex at 5th Avenue and 18th Street, but finally I decided to buy it. As I was reading along, soon I realized that it was becoming one of my favorite books. (It remains so.) Again, I’ll skip the details, but Chapters 7 and 8 provided some of my most cherished reading moments ever.

To grasp such a geeky memory, it helps to understand where I was in my life. In the fall of 1985, I had just graduated from NYU’s law school, I was living in Brooklyn, and I was working as a public interest lawyer in Manhattan. I had also become completely smitten with New York City. I doubt that I will ever again experience such deep affection for a place. If a big part of me will always be a New Yorker, then those early years in NYC will have a lot to do with it.

Time and Again spoke to that love of New York, and its story captivated me. Finney had a knack for writing the time travel tale — as his other books and short stories also attest — and he got it just right with this one. It may be as close to genuine time travel as I’ll ever get, a reading experience approached only by Stephen King’s 11/22/63 (2011). (In fact, in the Afterword to his book, King calls Time and Again “the great time-travel story.”)

So, if a tale of discovering olde New York is to your fancy, then you might give Time and Again a try. I think you’ll be glad you did. Don’t forget to close your eyes and see what Si Morley saw.

“Sons of Liberty”: Historical fiction vs. fictional history

From the standpoint of pure entertainment, I thoroughly enjoyed “Sons of Liberty,” a three-part mini-series depicting events leading up to the American Revolution, which premiered earlier this week on The History Channel.

The series is centered in Boston between 1765 and 1776. Major events such as the Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party, Battles of Lexington and Concord, and Battle of Bunker Hill are all there. Much of the everyday action takes place in the streets, taverns, and homes of old Boston, and that look-and-feel renders a gritty authenticity to the series, despite — as I’ll explain below — its many historical inaccuracies.

Among the various film depictions covering Boston’s Revolutionary history, this one vividly imagines what it must’ve been like to live there and then. So many of these historical sites have been preserved, and now I want to go visit them again.

Most of the iconic historical characters are present, too: The tension between rebellious, rough-edged Samuel Adams and financier/smuggler John Hancock receives a lot of play. Among the colonials, Dr. Joseph Warren, John Adams, Paul Revere, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington also get their share of air time. On the British side, governor Thomas Hutchinson and General Thomas Gage are most prominent, with Gage’s young wife Margaret playing a key role in the story. (You can check out the main cast members here.)

“Sons of Liberty” attempts to give these figures distinct, relatable personalities, with varying success. Sometimes they utter lines that made me think to myself, surely they didn’t talk like that back then, did they?

The series opens with Sam Adams escaping from British troops in a roof-hopping scene befitting an action show — fans of Jack Bauer in “24” will enjoy it — immediately telling us that “Sons of Liberty” will not be a stiff docudrama. This mini-series is meant to hold our interest, and its narrative flow moves along briskly.

Along the way, it takes a ton of historical, umm, liberties, many of which are explained in an excellent post by historian Thomas Verenna, “Discover the Truth Behind the History Channel’s Sons of Liberty Series” for the Journal of the American Revolution blog. In brief, a lot of the facts are wrong, the personalities of major characters are sometimes at odds with those of their real-life counterparts, and the British officers and soldiers behave much more brutally than the historical record indicates. Especially after reading critiques of “Sons of Liberty” by historians deeply familiar with the era, I’d suggest that it straddles the line between historical fiction and fictional history.

General Gage’s supposed trophy wife turns out to be much more than just another lovely face (Photo: DY)

That said, I really enjoyed this mini-series, and I’m sure I’ll watch it again. My suggestion is to view “Sons of Liberty” first, and then to read Verenna’s article. Its faults notwithstanding, the series breathes life into the major events and figures of the Revolutionary era. Verenna understands this when he diplomatically avoids slamming “Sons of Liberty” for its inaccuracies, even after documenting them:

The takeaway from this is that the Sons of Liberty program is highly entertaining historical fiction. We hope it energizes more people to study the Revolution and discover the truth behind these events. In many cases, the real story is better than fiction.

Recent Comments