“Sons of Liberty”: Historical fiction vs. fictional history

From the standpoint of pure entertainment, I thoroughly enjoyed “Sons of Liberty,” a three-part mini-series depicting events leading up to the American Revolution, which premiered earlier this week on The History Channel.

The series is centered in Boston between 1765 and 1776. Major events such as the Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party, Battles of Lexington and Concord, and Battle of Bunker Hill are all there. Much of the everyday action takes place in the streets, taverns, and homes of old Boston, and that look-and-feel renders a gritty authenticity to the series, despite — as I’ll explain below — its many historical inaccuracies.

Among the various film depictions covering Boston’s Revolutionary history, this one vividly imagines what it must’ve been like to live there and then. So many of these historical sites have been preserved, and now I want to go visit them again.

Most of the iconic historical characters are present, too: The tension between rebellious, rough-edged Samuel Adams and financier/smuggler John Hancock receives a lot of play. Among the colonials, Dr. Joseph Warren, John Adams, Paul Revere, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington also get their share of air time. On the British side, governor Thomas Hutchinson and General Thomas Gage are most prominent, with Gage’s young wife Margaret playing a key role in the story. (You can check out the main cast members here.)

“Sons of Liberty” attempts to give these figures distinct, relatable personalities, with varying success. Sometimes they utter lines that made me think to myself, surely they didn’t talk like that back then, did they?

The series opens with Sam Adams escaping from British troops in a roof-hopping scene befitting an action show — fans of Jack Bauer in “24” will enjoy it — immediately telling us that “Sons of Liberty” will not be a stiff docudrama. This mini-series is meant to hold our interest, and its narrative flow moves along briskly.

Along the way, it takes a ton of historical, umm, liberties, many of which are explained in an excellent post by historian Thomas Verenna, “Discover the Truth Behind the History Channel’s Sons of Liberty Series” for the Journal of the American Revolution blog. In brief, a lot of the facts are wrong, the personalities of major characters are sometimes at odds with those of their real-life counterparts, and the British officers and soldiers behave much more brutally than the historical record indicates. Especially after reading critiques of “Sons of Liberty” by historians deeply familiar with the era, I’d suggest that it straddles the line between historical fiction and fictional history.

General Gage’s supposed trophy wife turns out to be much more than just another lovely face (Photo: DY)

That said, I really enjoyed this mini-series, and I’m sure I’ll watch it again. My suggestion is to view “Sons of Liberty” first, and then to read Verenna’s article. Its faults notwithstanding, the series breathes life into the major events and figures of the Revolutionary era. Verenna understands this when he diplomatically avoids slamming “Sons of Liberty” for its inaccuracies, even after documenting them:

The takeaway from this is that the Sons of Liberty program is highly entertaining historical fiction. We hope it energizes more people to study the Revolution and discover the truth behind these events. In many cases, the real story is better than fiction.

Classic movie report: January 2015

A few weeks ago I declared as one of my New Year’s resolutions that I would watch more classic old movies. As compared to resolutions about training for a marathon run or learning a foreign language, this one didn’t exactly rank high on the difficulty or willpower meter. Nevertheless, I’m here to report that I’m doing pretty well on keeping it, aided by a winter cold that kept me more housebound than usual.

In fact, I’ve been on overdrive, with a big dose of historical and war movies:

Mister Roberts (1955) (4 of 4 stars)

Henry Fonda stars as Doug Roberts, a frustrated lieutenant serving on a rusty Navy cargo ship in the final year of the WWII’s Pacific Theatre. Roberts badly wants transfer to a combat ship, but his ambitions are blocked by a tyrannical captain (played by James Cagney) who refuses to approve his repeated requests. William Powell as the ship’s doc and Jack Lemmon as hapless Ensign Pulver round out a great cast of major supporting characters.

This is a superb, touching, and funny movie, evocative of its era but much, much more than a period piece. It’s easy to see why it was first such a hit on the Broadway stage, premiering in 1948 and running for years with Fonda in the lead role. It’s equally easy to watch the movie and imagine how it was staged as a play.

John Paul Jones (1959) (2.5 stars)

Robert Stack plays the America’s first Revolutionary War naval hero, Capt. John Paul Jones. I found it a bit of a disappointment. Though not without its interesting segments, the movie lacks dramatic pull.

Shenandoah (1965) (3 stars)

James Stewart stars in this Civil War story of Virginia farmer Charlie Anderson, who stubbornly tries to keep himself and his family out of the war until circumstances make it impossible to do so. This is an old fashioned Hollywood depiction of the Civil War, and Stewart makes it worth watching. I’ve watched this movie several times over the years, and I’m sure I’ll be doing so again.

The Flying Fleet (1929) (3 stars)

This is a historical nugget, a silent movie about the early years of naval aviation, featuring fascinating film footage of old Navy biplanes and the U.S.S. Langley, the very first American aircraft carrier. Co-stars Ramon Novarro and Ralph Graves are young pilots who compete for plum missions and for the attentions of Anita Page, a hottie of the silent film era.

The Flying Fleet was co-authored by Frank “Spig” Wead, a naval aviation pioneer whose colorful career would later be the subject of The Wings of Eagles (1957), starring John Wayne. It was intended to glamorize and promote naval aviation, which was fighting for legitimacy among traditional, hidebound Navy leaders and the general public. Here’s a trailer:

Visiting Berlin during the Cold War

Twenty-five years ago, the Berlin Wall fell, marking a symbolic end to the Cold War. This week’s observances of that event have prompted memories of visiting Berlin in May 1981. A few weeks earlier, I had finished my final undergraduate semester at Valparaiso University’s study abroad program in England, and Berlin was among my stops on a whirlwind trip through parts of the European continent.

In 1981 the Cold War very much remained a defining element of international relations, and divided Berlin captured the heart of the era. Although I was but one of millions of tourists to the city during that time, it felt adventurous to be splitting off from my friends for a brief solo trip there.

I’ve included some of my grainy snapshots, temporarily plucked from my study abroad photo album.

It was possible to get a one-day pass to travel from democratic West Berlin into Communist East Berlin. Via the Allied Checkpoint Charlie, you were processed through to the other side, under the watchful eyes of East German guards. You also had to exchange a minimum amount of money, and what you didn’t spend had to be “donated” to the East German government before crossing back to the west side.

Whereas life in the heart of West Berlin seemed loud and decadent, the streets of East Berlin felt lifeless under Communist rule — as drab and dreary as the photo above suggests.

There also wasn’t a lot to spend one’s money on; the (excellent) museums were free and food options were sparse. As my day in East Berlin drew to a close, I still had a fair amount of money left, and I didn’t want to simply hand it over to the East Germans. I thought I had lucked out when I spotted a bookstore, figuring I’d buy a book as a souvenir. However, the only title in English, displayed prominently for folks like me, was a hardcover edition of the complete works of Lenin. So I bought it! I would spend the rest of my European jaunt lugging around that big volume. Though I did bring it home with me, I cannot recall ever reading it before giving it away many years ago!

The specter of the Second World War was also very much present. I did a quick tour of the Reichstag building that housed the German parliament until 1933, when a fire of unknown origin prompted the Nazi government to suspend most of the individual rights contained in the nation’s constitution. I also visited the Olympic Stadium in which African American track and field star Jesse Owens won his gold medals, achievements said to have undermined the myth of Aryan superiority.

I’m very glad that I made Berlin a stop on my European itinerary, but there was something about the city that made me uneasy. I think I felt the energy of so much terrible stuff happening there during the city’s 20th century life. I would return to Berlin in 2011 when I attended a conference at Humboldt University, and I couldn’t shake that disturbing sense even though it had changed dramatically. Some places just have a certain discomforting feel, you know?

On my nostalgia addiction

Random nostalgia: The Cozy Soup ‘n’ Burger, Broadway & Astor Place, NYC, site of countless downed burgers during law school and thereafter (Photo: DY)

As someone who succumbs easily to nostalgia — supposedly this is common among those of us born under the Cancer sign — this blog permits me to hop into my personal time machine on a regular basis. And Throwback Thursday is a Hallmark card of an invitation to switch that machine into overdrive. Today I’m going to ponder why I find such indulgences so appealing.

It hurts so good?

Last year, John Tierney, writing for the New York Times, served up a fascinating piece on the role of nostalgia in our lives. He featured the research of psychology professor Constantine Sedikides (U. Southampton, U.K.), who challenges the popular notion that nostalgia must be associated with sad melancholy. Here’s a snippet:

Nostalgia has been shown to counteract loneliness, boredom and anxiety. It makes people more generous to strangers and more tolerant of outsiders. Couples feel closer and look happier when they’re sharing nostalgic memories. On cold days, or in cold rooms, people use nostalgia to literally feel warmer.

Nostalgia does have its painful side — it’s a bittersweet emotion — but the net effect is to make life seem more meaningful and death less frightening. When people speak wistfully of the past, they typically become more optimistic and inspired about the future.

He included a thought-provoking perspective from Dr. Sedikides:

“Nostalgia makes us a bit more human,” Dr. Sedikides says. He considers the first great nostalgist to be Odysseus, an itinerant who used memories of his family and home to get through hard times….

Writer and online “salon keeper” Stacy Horn, in her book Waiting for My Cats to Die: a morbid memoir (2001), calls nostalgia “both a self-inflicted wound and the morphine you take for the pain – a perfect reprieve from the cold, cruel light of an untampered-with day. It hurts, but it’s a good hurt.” I tend to agree, seeing nostalgia as a simultaneous pleasure/pain kinda thing.

Nostalgia scale

The online version of the Times article linked to Dr. Sedikides’s webpage. The webpage includes a questionnaire called the “Southampton Nostalgia Scale,” which defines nostalgia as a “sentimental longing for the past.”

I answered the survey questions, and I clearly score off the charts. I think about my past a lot. I think about historical events and eras a lot, and I yearn to experience them, even if they preceded me by decades. I probably could get soggy about the coffee I had with breakfast yesterday if the moment was right.

The weird thing is, I’ve been this way since I was a kid. As a grade schooler, I would get nostalgic about family vacations to visit relatives in Hawaii!

Take my “Yearbook Test”

Here’s my personal test for measuring one’s propensity for nostalgia: I call it the “Yearbook Test.”

Spend some time with a college or high school yearbook, maybe one grabbed from a friend’s bookshelf or rescued from the bargain bin at a used bookstore. Although it can be from a school you attended, it shouldn’t be one from your years there or the years immediately preceding or following them. (In other words, it cannot overlap with anyone you knew from your own student days.)

Do you find yourself feeling like you “know” people in the yearbook? Do you start imagining their lives? Can you guess at the groups and cliques that may have formed up? Do you find yourself wanting to step back into that time and place to experience it personally, just to see what it was really like?

If you’re inclined to answer yes to these questions, then I’d bet a fair amount of change that you’re a nostalgia junkie. I mean, let’s face it, if you can get all sentimental over the student experiences of those from another era, then you’re a goner when it comes to nostalgia.

For the record, I’ve used ebay to obtain a smattering of old yearbooks from my undergraduate alma mater, Valparaiso University, and from my law school alma mater, New York University, dating from the early to mid-20th century. I can get lost in them for hours. On occasion, I’ve Googled names of students in an attempt to see what became of them.

In other words, I’m hopeless.

History buff

I have no doubt that my nostalgic tendencies dovetail with my enjoyment of history. My status as a history buff has a strong emotional component to it. For example, last year I wrote about my affinity for the 1980s mini-series “The Winds of War.” The story starts in 1939, as war clouds are swirling about Europe. It follows the fortunes of the Henry family, headed by U.S. Navy officer Victor “Pug” Henry, along with his wife Rhoda, sons Warren and Byron, and daughter Madeline.

Joining them as major figures are renowned Jewish author and retired professor Aaron Jastrow and his niece, Natalie, who are living in an Italian villa. Also prominent is Pamela Tudsbury, a young British woman who travels the globe helping her father, foreign correspondent “Talky” Tudsbury, as well as foreign service officer Leslie Slote.

“The Winds of War” qualifies as a sweeping epic. It opens with Europe on the brink of another war, and it continues on through the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Throughout the story, the major characters and others cross paths, move apart, face life-threatening danger, and fall in and out of love, in places as disparate as London, Berlin, Italy, Portugal, Washington D.C., Hawaii, the Soviet Union, and the Philippines, among many others.

I find myself caught up in that dramatic sweep, imagining the lives of the characters and the look & feel of the era. I watch the full mini-series roughly once a year, and it has an odd, comforting effect on me.

How “accurate” is our nostalgia?

I understand how we often create memories that make certain times appear a lot rosier in the rear view mirror. I know that the past is rarely what it’s cooked up to be.

When it comes to feeling sentimental about historical eras, I’d love to visit 19th century London or 1920s New York. But would I actually like to live during those times, for the long haul, with no “go back” button in the event I find myself, say, in a Dickensian workhouse or a Lower East Side tenement? And despite my affinity for the Second World War years, for an American of Japanese descent, a time machine return to that period would not be desirable.

As for my own past, there are few times in my life that I’d truly like to live over again, not because I’ve had a bad life, but rather because the “do overs” I yearn for — the ones with the benefits of wisdom, hindsight, and maturity — are impossible. I was reminded of this last week, when a brief Facebook exchange with college chums led to recounting favorite eateries near the campus. Now, if someone today offered me a few years to go back to school, think big thoughts, and enjoy campus life, I’d happily take it. But would I want to return to the post-adolescent anxieties of (in my case barely) early adulthood? No thanks!

So, the bottom line: I’ll continue to indulge my nostalgic tendencies. But at least I know that the rear view mirror often serves up a distorted picture.

***

Related post

Time travel: Some favorite destinations (2013)

***

This post borrows several big chunks from a 2013 piece published on my professional blog, Minding the Workplace.

Throwback Thursday: Where were you when Nixon resigned?

For those of you around during August 1974, where were you during when President Richard Nixon resigned from office in the midst of the Watergate scandal?

At the time, I was in high school, heading into my sophomore year. That night I happened to be watching a football game. The Jacksonville Sharks were playing the Hawaiians, both of the fledgling World Football League, an upstart, ragtag operation that was challenging the established NFL. The game was interrupted by Nixon’s resignation’s speech, which made for an odd return to the televised game action following such a momentous event!

For readers too young to understand the Watergate scandal, or for the sprinkling of international readers thankfully spared the ongoing saga back then, Nixon got in trouble when his Administration was linked to an illegal break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington D.C.’s Watergate Hotel during the 1972 election campaign. As is so often the case, the cover up was worse than the initial sin, and it led right to the Oval Office.

The Washington Post took the lead on investigating the Watergate scandal, and it served to launch the careers of two unknown reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

The movie “All the President’s Men,” starring Robert Redford (Woodward) and Dustin Hoffman (Bernstein), manages to tell the story of the Post‘s investigation with a sense of detail and drama that conveys the gravity of this historic event in American government and politics. It still holds up as an excellent movie.

I’m just a 20th century kinda guy

When I think about the cultural and historical markers in my life, I quickly reach the conclusion that I’m a 20th century kinda guy. Born in 1959, and given my appreciation for history, the last century is my default lens on the world.

My personal culture

My pop culture worldview is still partying like it’s 1999.

If not earlier! For example, when it comes to popular music, my tastes stop somewhere in the mid-80s, and I’m more drawn to composers and performers of the early and middle 20th century — the Gershwins, Cole Porter, Sinatra, the Big Bands, Rodgers & Hammerstein, etc. — than any other era.

And while current television dramas are generally superior to most of their predecessors, I’ll take yesterday’s classic sitcoms — “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” “MASH,” and yes, even “Hogan’s Heroes” — over “Two and Half Men” and other popular shows today. As for the big screen, I’ll gladly opt for a rich array of oldies, while passing on the dreck coming out of Hollywood now.

As far as my Chicago sports fandom goes, give me the 1985 Chicago Bears, the 1990s Chicago Bulls, the 1969 Cubs, the 1984 Cubs, the 1983 White Sox…okay, it’s a mixed bag.

In terms of technology, I’ll take DVDs over streaming, CDs over MP3 (closer call), real books over e-books (though I get the convenience & cost factor), and Word Perfect 5.1 for DOS over anything to do with Microsoft Word. I’m not that crazy about cellphones, and I don’t permit my students to use laptops in my classes. (In a big bow to the 21st century, I believe the iPad is one of the most brilliant devices ever made.)

And what of the bigger picture?

Centuries are marked by the turn of a calendar, but their essence is defined by core events. For me, the 20th century era — at least from an admittedly American perspective — began in 1903, when the Wright Brothers successfully flew their primitive airplane in the dunes near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. It ended with the attacks of September 11, 2001. (Hmm, both events centered on the use of airplanes…)

When it comes to grasping history and current events, I see how we’re still strongly influenced by decisions and events of the last century. World diplomacy in 2014 has the scary look & feel of Europe in 1914, and the two world wars continue to shape international relations. And if you want a milestone year for understanding the path toward America’s present domestic and international political status, then take a close look at 1980: The election of Ronald Reagan and the Iranian hostage crisis captured the nation’s conservative turn and anticipated its post-Cold War preoccupation with the Middle East.

Somewhere a place for us

I happen to believe there’s still a place in this world for those of us whose outlook on things reaches back into the last century. If not, whatever. I’ll just pop that best-of-the-80s cassette back into my Walkman and try to get over it.

“The Big Lift”: World War and Cold War meet up in Berlin

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the victorious Allies divided the city of Berlin into zones controlled by the Americans, British, French, and Russians. The first major international crisis of the Cold War was triggered by a 1948 Russian blockade of Western goods and supplies into Berlin, and resulted in the Western countries joining together in the Berlin Airlift, a massive airlift of food, fuel, and other necessities for a German populace still suffering from the ravages of the war. The blockade was lifted in 1949, with Germany divided into separate Eastern and Western states.

The Big Lift (1950) is a raw, authentic, fascinating movie built around the Berlin Airlift. Montgomery Clift leads the cast as an Air Force sergeant who becomes involved with a Berliner, played by German actress Cornell Borchers. Paul Douglas, in a lead supporting role, plays an American sergeant who carries deep anger and contempt toward the Germans. All other military roles were played by actual members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

The Internet yields mixed reviews for this movie, mostly due to supposedly uneven plot lines. However, I find the personal stories to be smartly layered into the time and place, and both lead and supporting cast members deliver convincing performances. The film’s interactions between the Americans and Germans are emotionally and politically complex, capturing how tensions fueled by both the Second World War and the Cold War shaped personal relationships.

But the real star here is post-war Berlin, where most of the movie was filmed in 1949. Some four years after the war ended, Berlin was still rebuilding from Allied bombings, and much of the city remained as piles of rubble. The movie wholly captures that reality. In addition, the aerial shots of Allied supply planes flying into and taking off from Berlin’s Templehof airport are like a documentary from the era. Scenes in the Berlin subway and city streets are gritty and real. You feel like you’re watching history.

The movie was produced as a portrayal of a major international event, but now it serves as a unique, remarkable time capsule. The Big Lift gets my vote as one of the most underrated historical dramas ever. I just finished a repeat viewing, and I’m sure it won’t be the last time.

***

Go here for a version posted to YouTube.

Go here for the Wikipedia article on The Big Lift (spoiler alert on the summary)

Go here for the Wikipedia article on the Berlin blockade.

“Grand Central”: Postwar stories from one of the old familiar places

I’ve just started reading Grand Central: Original Stories of Postwar Love and Reunion (2014), a newly-released anthology of short stories by ten writers, with the iconic train station playing a role in each one. Last night I read “The Lucky One” by Jenna Blum, author of two very successful novels, Those Who Save Us and The Stormchasers. I count Jenna among my dear friends, so perhaps I’m biased, but if her contribution is a harbinger of things to come, I’m in for a treat.

I began with Jenna’s story because, well, I saw it as sort of a test. WWII. Train station. Love and reunion. In the wrong hands, such a collection could easily become a soggy nostalgia fest, conjuring up images of a couple having a final embrace before the one left behind runs along the departing train. Because I’m a big fan of Jenna’s work, I figured her story would give me an idea of what to expect.

Jenna’s “The Lucky One” is about a Jewish concentration camp survivor who works at Grand Central’s famous Oyster Bar restaurant. He sees a customer who looks like his late mother. . . .

Enough said. I’ll simply opine that “The Lucky One” is a superb, knowing, heartfelt contribution from a writer whose ability to tell a great story with nuanced emotional intelligence is one of her distinguishing gifts. It also is the work of someone who learned about the Holocaust by interviewing survivors for Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah history project. Jenna has infused a lot of historical understanding into her short story.

Okay folks, I know I’m betraying my own limitations when I confess that I cannot recall ever diving into a volume of short stories with a cover showing a couple kissing in a train station! But I will be the loser if I don’t spend more time with this one. And I have a strong feeling that the next time I step into Grand Central Station, some of these tales will come to mind.

June 6, 1944: Why it matters for those of us born much later

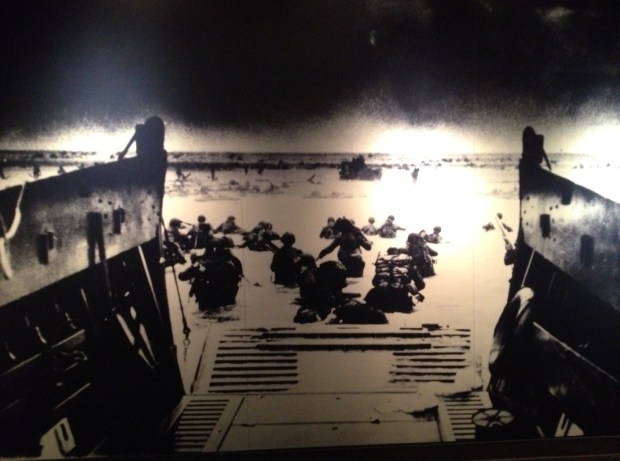

Seventy years ago, Allied forces landed on the beaches of Normandy, France, signaling the beginning of the major campaign to reclaim Europe from Hitler’s Germany. If you’ve ever wondered how terms such as “D-Day” and “first wave on the beach” became parts of our cultural vocabulary, look no more.

The veterans of D-Day are aging, and many have passed on. But this remains a signature event in history. Had the invasion failed and the Allied forces been pushed back across the English Channel, the war likely would’ve gone on for years. Instead, it ended the next May in Europe and the next September in the Pacific.

German defenses watched Allied troops landing on Normandy beaches from these fortifications (from National WWII Museum, New Orleans)

Most of us have been spared the experience of armed combat, but if you want a sense of what it was like to be in that first wave of troops on the beach, the opening sequence of Saving Private Ryan, Steven Spielberg’s 1998 depiction of a squad of American soldiers assigned to a special mission, is about as close as you’d want to get.

If you’d prefer popular historical overviews of D-Day, then Stephen Ambrose’s D-Day (1994) and Walter Lord’s The Longest Day (1959) are good book choices. The 1962 screen adaptation of Lord’s book (also titled The Longest Day), while very much a Hollywood war movie, tells the story well, too.

In my previous post, I observed that some of us would benefit by finding greater meaning in the common, ordinary, and mundane pieces of our lives, rather than always working toward or anticipating the next big event. Many of the men who returned home from D-Day and other places of battle understood that notion implicitly. They had seen enough of the world’s conflicts and drama; many wanted nothing more than to lead quiet, comfortable, and relatively uneventful lives.

I try to remember this whenever I look back at WWII, while simultaneously yearning for a greater sense of shared purpose in our fragmented society. It’s awfully easy to romanticize the war era through a rose-colored lens some 70 years old. But I can’t imagine anyone who survived the beaches of Normandy getting too soggy about a global war that left millions of casualties. D-Day matters for a lot of reasons, not the least of which is how it reminds us of the blessings of living in peace.

In praise of the mundane and slow blogging

Commenting on my previous dramatic, pathbreaking post about coffee (NOT), one of my friends remarked on Facebook that I had a knack for making even mundane subjects sound engaging and interesting. That’s a real compliment for a personal blog — thank you, Holly!

That said, “mundane” isn’t exactly what inspired blogging, which first became popular roughly a decade ago as a way to publish breaking news and commentary on major events. In addition to serving that journalistic purpose, blogging also has grown into a medium for synthesizing information and for sharing analysis and opinion.

In any given week, I read a fair share of blogs for all of these purposes. And through my professional blog, Minding the Workplace, I attempt to contribute to that dialogue by writing about issues of employee relations, workplace bullying, and psychological health at work. On occasion, I even help to break a story within my realm of work.

However, I also find myself increasingly drawn to blogs about everyday life, hobbies, travel, memoirs, TV shows, books, sports, avocations, and anything else that isn’t about hard news, analytical thinking, and conflict. They offer interesting, entertaining, and sometimes fascinating windows into our daily lives. And since launching this personal blog last fall, I’ve come to enjoy writing about some of the more common or ordinary aspects of life, two words often used to define mundane.

Understanding “slow blogging”

To characterize these less momentous uses of blogging, I reference the term slow blogging, the philosophy and practice of which has been beautifully articulated in the Slow Blogging Manifesto by software designer and writer Todd Sieling. (He hasn’t updated his blog in years, but this post alone is worth keeping it online.) Here are a few snippets:

Slow Blogging is a rejection of immediacy. It is an affirmation that not all things worth reading are written quickly, and that many thoughts are best served after being fully baked and worded in an even temperament.

***

Slow Blogging is a reversal of the disintegration into the one-liners and cutting turns of phrase that are often the early lives of our best ideas.

***

Slow Blogging is a willingness to remain silent amid the daily outrages and ecstasies that fill nothing more than single moments in time, switching between banality, crushing heartbreak and end-of-the-world psychotic glee in the mere space between headlines.

The happily mundane

Maybe we need to make a more prominent place for slow blogging about the common and ordinary. We all want to live good, rewarding, purposeful lives. Many of us have a tendency to frame this in terms of milestones, such as major work accomplishments or family events. But perhaps we should spend more time appreciating and reflecting upon the everyday stuff as part of our search for that meaning.

So I leave you with this photo of my three-unit condo building in Jamaica Plain, Boston (“JP” to locals), taken on a dreary, wet, overcast day earlier this year. Having moved there in 2003, this is the longest I’ve lived anywhere since my childhood. Although my condo is nothing elaborate in terms of space, views, furnishings, or architecture, it’s a good home.

Equally important, as someone who doesn’t own a car, my place is a quick walk to subway (aka the “T” in Boston) and bus lines. The T’s Orange Line takes me into the city’s downtown area. Logan Airport and South Station (Amtrak) are short T rides away, a boon to frequent travelers such as myself.

My home is close to JP’s shops, stores, and restaurants. And when I’m hungry and don’t want to cook heat up something, I can bop across the street to the City Feed and Supply Store for a sandwich, order a pizza from Il Panino, or call in for Chinese delivery from Food Wall.

The photo above doesn’t capture the beauty of JP, a diverse, picturesque neighborhood in the southwest region of Boston. I was reminded of this a couple of weeks ago when I slept past my subway stop and got off at the next station, still in JP. To get home I walked along the Southwest Corridor Park, a linear park that runs roughly parallel to the T tracks through a long stretch of the city. It was a beautiful walk, the kind that makes you think “urban oasis.”

These are simple things that can make for an enjoyable day, and pleasant reminders — even for those of us too caught up in destinations at times — that the journey counts for a whole lot.

Recent Comments